Major broadband satellite operator Viasat has officially committed to launching one of its powerful next-generation Viasat-3 satellites on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, set to occur sometime between 2020 and 2022.

Nine days after Swedish satellite communications company OvZon made its own announcement of a Falcon Heavy launch contract, Viasat’s Falcon Heavy selection marks SpaceX’s third commercial launch contracted on the nascent heavy-lift rocket.

Viasat, SpaceX Enter Contract for a Future ViaSat-3 Satellite Launch: https://t.co/DOlUIcgPQF Photo Credit: @SpaceX #VS3 #ViasatInc pic.twitter.com/vM1duf1x41

— Viasat Inc. (@ViasatInc) October 25, 2018

In 2016, Viasat announced that a planned launch contract with SpaceX for a heavy Viasat-2 satellite would be transferred to Arianespace to avoid major delays caused by Falcon Heavy’s torturous path to launch debut. As a contractual compromise, Viasat optioned Falcon Heavy for one of three launches of its three next-generation Viasat-3 satellites, an option that was exercised to become a true launch contract today.

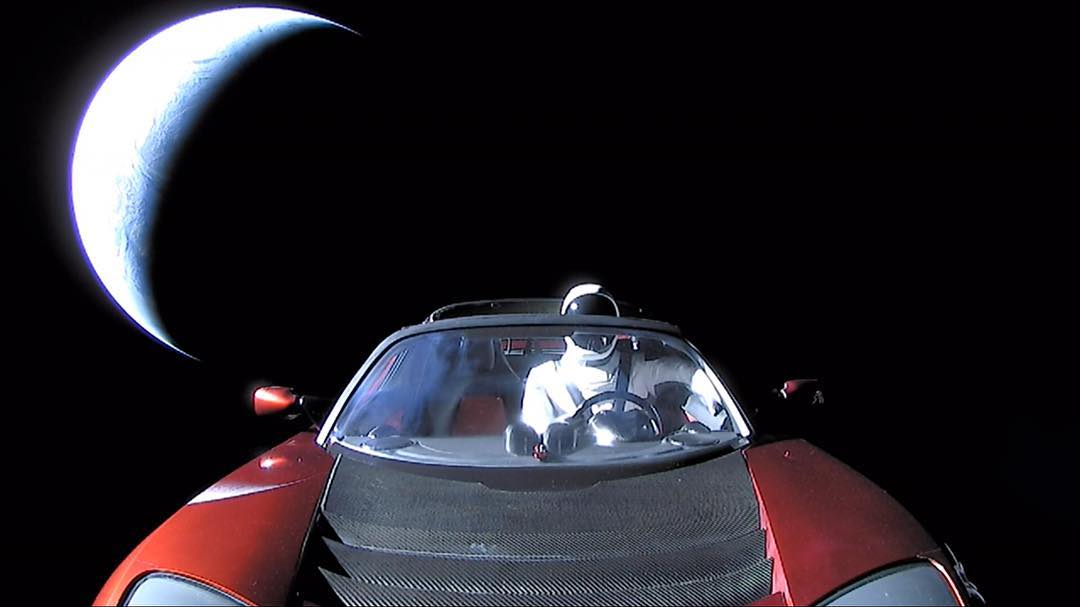

Viasat’s 2016 decision ultimately proved to be expertly calculated, and SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy was effectively put on the back burner after a September 2016 failure, pushing its launch debut into 2018. Delays aside, Falcon Heavy ultimately debuted in February 2018 with a mission that both became a bit of an icon – CEO Elon Musk’s own Tesla Roadster and a SpaceX-suit-wearing mannequin were sent beyond Earth’s orbit – while also successfully demonstrating a particular launch capability of interest to certain high-value customers.

Falcon 9 B1046 returned to Port Canaveral in mid-August after the first Block 5 booster reuse, hopefully the first of dozens or even hundreds to come. (Tom Cross)

» data-medium-file=»https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/B1046-return-2-081218-Tom-Cross-6c-feature-300×144.jpg» data-large-file=»https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/B1046-return-2-081218-Tom-Cross-6c-feature-1024×491.jpg» src=»https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/B1046-return-2-081218-Tom-Cross-6c-feature-748×359.jpg» width=»748″ height=»359″ align=»left» title=»B1046 return #2 081218 (Tom Cross) (6)(c) feature»>

Coasting to success

During Falcon Heavy’s maiden launch, SpaceX took it upon itself to use the unique opportunity – a mission where the only payload at risk was functionally worthless – to test a number of technologies that the company had yet to personally prove out. In order to place certain payloads in orbits as convenient, efficient, and high-energy as possible, rocket upper stages can sometimes be required to spend hours orbiting Earth between two or more engine ignitions and burns.

Once successfully in orbit, the performance potential of upper stages grows dramatically thanks to the increased efficiency of vacuum-optimized rocket engines and major improvements in thrust-to-weight ratios, having already consumed a majority of the fuel and oxidizer loaded prior to launch. The problem is that keeping a large upper stage alive in orbit – while preserving enough liquid propellant to perform its job – is extraordinarily difficult. Notably, the thermodynamic environment alone is a massive hurdle – aside from expanded power supplies, radiation-hardened or resilient avionics, and multi-engine-restart capabilities, some combination of coolers, insulation, and/or tank stirrers must be involved to prevent SpaceX’s already-supercooled liquid oxygen and kerosene (RP-1) from changing phases into a solid or a gas.

During Falcon Heavy’s debut, SpaceX demonstrated what must have been a nearly flawless six-hour coast of the rocket’s Falcon 9 upper stage – in the last four months alone, SpaceX has officially received three new Falcon Heavy contracts all hoping to take advantage of that long-coast capability. Critically, this allows SpaceX to send large satellites directly or almost directly to geostationary orbits (GEO) instead of a more common transfer orbit (GTO), saving satellites from spending weeks or months completing their own orbit-raising maneuvers and the hundreds or thousands of kilograms of propellant they require.

SpaceX’s updated Falcon Heavy manifest:

– Arabsat 6A (NET early 2019)

– STP-2 (NET 2019)

– AFSPC-52 (NET September 2020)

– Ovzon (NET Q4 2020)

– Viasat-3 (2020-2022)Pending confirmed payload:

– Inmarsat— Michael Baylor (@nextspaceflight) October 25, 2018

Inmarsat, another long-time customer still in possession of old agreements for Falcon Heavy launches, may be next in line to announce firmer launch decisions for Global Xpress and Inmarsat 6 satellites once penciled in for Falcon Heavy in a 2014 contract – flight-ready hardware is expected to be ready for launch in the 2019-2021 timeframe.

For prompt updates, on-the-ground perspectives, and unique glimpses of SpaceX’s rocket recovery fleet check out our brand new LaunchPad and LandingZone newsletters!